The barricades came down yesterday morning, when the temporary walls obscuring Mark Wallinger's State Britain were finally removed. Running the length of the central spine of Tate Britain is a near-perfect, life-sized replica of the one-man camp that peace campaigner Brian Haw occupied on Parliament Square between June 2001, when he first began his protest against the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq, and the night in May 2006 when the police removed almost the entirety of Haw's belongings.

The barricades came down yesterday morning, when the temporary walls obscuring Mark Wallinger's State Britain were finally removed. Running the length of the central spine of Tate Britain is a near-perfect, life-sized replica of the one-man camp that peace campaigner Brian Haw occupied on Parliament Square between June 2001, when he first began his protest against the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq, and the night in May 2006 when the police removed almost the entirety of Haw's belongings.In between, the twin towers fell, Afghanistan was invaded, and sanctions against Iraq turned into occupation and civil war. London and Madrid were bombed, and the 2005 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act was passed, forbidding any unauthorised protests within a kilometre of Parliament Square. It was said that terrorists might use protests such as Haw's as a cover for their activities - though it appeared to have been designed principally to move Haw on.

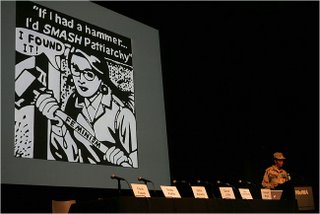

Over the years, Haw's public protest opposite the Houses of Parliament grew to become a rambling, gap-toothed, 40-metre-long wall of banners, placards, rickety, knocked-together information boards, handmade signs and satirical slogans. Banksy donated a big painting of soldiers. Sun-bleached rainbow peace flags flapped overhead. The placards declaimed "You Lie Kids Die BLIAR" and "Christ Is Risen Indeed!". Road-spattered appeals to motorists to "Beep For Brian" stood beside an accumulation of material that could only be read or understood close-up. Photocopied warzone reports, commemorative crosses, entreaties and signs that have crept in from other people's protests - "Pensioners want a slice of the cake, not crumbs" - compete, and an estate agent's board has even found its way amongst the piles of stuff on the far side of Haw's placards, the accumulation of a near-five-year tenure.

Lovingly copied and recreated, this has all made its way into Wallinger's work. All that is missing is the indomitable Haw himself, with his megaphone and his badge-encrusted floppy hat. He is still camped on the grass opposite parliament, but now occupying only a fraction of the space he once had. A few days before Haw's stuff was all taken away, Wallinger took hundreds of photographs of the entire, splendidly ramshackle, ranting, unmissable eyesore on which he based his reconstruction. Here is an impromptu, cobbled-together monument to a "fallen comrade", constructed from a plastic traffic cone, several lengths of taped-together garden cane and a homemade flag. There, a group of dolls in Victorian dresses is lying beside a plastic baby with missing arms and legs, bloodied with paint. Mutilated soft toys, placard-waving and card-carrying teddy bears - bears against bombs, bears saying "too much to bear" - and soft toys piled in a paper coffin.

It all has a cumulative, creepily sentimental horror. It also, weirdly, reminds one of all sorts of artwork one has seen before: the installations of Mike Kelley; the placards, swathes of photocopied material and detritus of Thomas Hirschhorn. With its recreation and representation of an individual's lair, and the stuff they surround themselves with - Haw's Tesco biscuits are here, a sleeping bag sandwiched between layers of tarpaulin, his rolling tobacco and his flagons of drinking water, and what looks like pee - it is not unlike the fictional habitats of Mike Nelson's work, or even of some of Beuys's placards and survival packs.

State Britain could be interpreted as a continuation of Haw's protest by other means, in such a place and in such a way as to mock a law designed to curtail our freedom to protest. The whole thing is a trompe l'oeil fabrication, a still life, a 2007 history painting - the modern equivalent of Géricault's Raft of the Medusa, Goya's Third of May and Manet's Execution of the Emperor Maximillian, all of which referred in contentious ways to world events. Taken as a whole, it is the sort of thing one might find documented in Jeremy Deller's Folk Archive, his collection of the amateur and the inadvertent.

For State Britain, Wallinger has also taped a line on the floor, indicating an arc of the kilometre cordon as it passes through the gallery. It first appears under a display of wrapping paper in the Tate Britain shop, crossing the floor and disappearing under a display of art-technique manuals. It crosses a room currently dominated by a bust of TE Lawrence, hitting the wall beneath Jacob Kramer's Jews at Prayer; it passes Jacob Epstein's alabaster Jacob and the Angel, and speeds beyond Nicholas Hilliard's portrait of Elizabeth I. It slides past a vitrine displaying the first English translation of the Qur'an, published in 1649, just four months after the beheading of Charles I. Finally, the line hits the wall under George Stubbs's 1785 painting of Reapers, his immaculately turned-out peasants decorously working the farm. The line may be an arbitrary slice through the building, but it adds to the effect, and creates its own resonances and echoes. The line joins as much as it divides, and places Wallinger's work in a conversation with the rest of Tate Britain.

Brian Haw is a driven individual, whose entire life is given over to his kerbside protest. To ask what drives him, apart from his moral and political convictions, is to diminish the exemplary nature of his protest, whatever one might think of the manner of his dissent. Yet he is not unlike the figures Wallinger has focused on before. Throughout his career, Wallinger has returned again and again to the theme of Englishness as a trope for identity, and to the events, myths, faiths and individuals that make up a sense of national belonging. In Passport Control, 1988, Wallinger graffitied over his own portrait, turning his photo into various ethnic stereotypes (orthodox Jew, Arab, Chinese). In his 2000 film Threshold to the Kingdom, he showed passengers emerging through passport control at London City Airport, in slo-mo and to the strains of Allegri's setting of the 51st Psalm. We see their ecstatic expressions and relief, as though they had indeed passed a spiritual, as much as a bureaucratic, test. The film is deeply sad, a miserable miracle.

Everyone from the Women's Institute to the far right has claimed William Blake's Jerusalem for themselves, but in his own work Wallinger reminds us of Blake's radicalism; he has used the word Jerusalem as if it were revolutionary graffiti, spraying it over his own rendering of a painting by George Stubbs.

Wallinger once recorded a performance of the comedian Tommy Cooper and played it backwards, reflected in a mirror, a sort of loving homage to Cooper's anarchic stage confusion. Recreating Haw's protest is itself a kind of reversal, as well as a duplication. By bringing the protest inside an institution, Wallinger gives us a chance almost to freeze it, presenting it as a simulacrum of itself.

He is very good at teasing out meanings and metaphors. In a number of paintings and videos, he has analysed the culture of horse breeding and racing - in which he saw the dynamics of race, sex and class at work. In 1994, he bought a real live racehorse, calling it A Real Work of Art and registering his own racing colours.

Looking at State Britain, I am reminded of numerous earlier works by the artist. Haw's protest stems from his evangelical faith. In several works, including 1999's Ecce Homo, Wallinger has examined what kind of faith an artwork might now exemplify or entail. Ecce Homo placed a cast of an anonymous young man dressed as Christ on the empty plinth in Trafalgar Square in 1999. Wallinger's Christ was not just an everyman, he was a stand-in. What, I asked a few months ago on these pages, would be the reaction to the placing of such an overt Christian symbol there today? It might well be taken as a provocation. Certainly, it is within the sacred kilometre.

Is State Britain a protest, a readymade, a simulation or an appropriation? It is all these things - an installation, an institutional critique, an example of relational aesthetics. It touches all bases, without becoming tedious or hectoring. The title may be a poor pun, but the work itself is clever and barbed. It makes us think of the mores of recent installation art, about the "public" nature of a space such as Tate Britain's Duveen Galleries and about the Britishness of the gallery itself - what is and is not exhibited here? State Britain raises more questions than it answers, but it is not glib. While Haw's placards announce the campaigner's beliefs, Wallinger takes a step back from the slogans themselves. Walking among the banners, you realise you look at them differently here.

Wallinger is asking us to view his recreation of Haw's stuff as art (even if some of it, like Banksy's image, already is art of a sort); he is not asking us to see Haw himself as an artist. Instead, he wants us to think more in terms of place and context - another of modern art's modes, the site-specific. In an accompanying exhibition publication, Wallinger presents a montage of writings - taken from George Orwell and Thomas Jefferson, the journalist Henry Porter and Tony Blair himself ("When I pass protesters every day at Downing Street, and believe me, you name it, they protest against it, I may not like what they call me, but I thank God they can. That's called freedom").

Since the 1960s, many artists, from Hans Haacke to Daniel Buren, Cildo Meireles to Allan Sekula, have made work which offers a critique of the institution that houses it, and the structures, financial and ideological, that support it. However critical such art may itself be, it also serves to highlight the institution's liberalism, by allowing it to be there in the first place. Such inclusiveness, as Susan Sontag argued, defuses the very criticism being offered. What State Britain offers is a sort of portrait of British institutions at a time of war, of the lip service government pays to dissent, on the attacks being made on our freedoms in the name of security, on the impotence of protest and of art itself as a form of protest. How rich this work is, and how saddening our state.