Feminist Art Finally Takes Center Stage, NYTimes

“Well, this is quite a turnout for an ‘ism,’ ” said the art historian and critic Lucy Lippard on Friday morning as she looked out at the people filling the Roy and Niuta Titus Theater at the Museum of Modern Art and spilling into the aisles. “Especially in a museum not notorious for its historical support of women.”

Ms. Lippard, now in her 70s, was a keynote speaker for a two-day symposium organized by the museum that was titled “The Feminist Future: Theory and Practice in the Visual Arts.” The event itself was an unofficial curtain-raiser for what is shaping up as a watershed year for the exhibition — and institutionalization, skeptics say — of feminist art.

For the first time in its history this art will be given full-dress museum survey treatment, and not in just one major show but in two. On March 4 “Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution” opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, followed on March 23 by “Global Feminisms” at the Brooklyn Museum. (On the same day the Brooklyn Museum will officially open its new Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art and a permanent gallery for “The Dinner Party,” Judy Chicago’s seminal proto-feminist work.)

Such long-withheld recognition has been awaited with a mixture of resignation and impatient resentment. Everyone knows that our big museums are our most conservative cultural institutions. And feminism, routinely mocked by the public media for 35 years as indissolubly linked with radicalism and bad art, has been a hard sell.

But curators and critics have increasingly come to see that feminism has generated the most influential art impulses of the late 20th and early 21st century. There is almost no new work that has not in some way been shaped by it. When you look at Matthew Barney, you’re basically seeing pilfered elements of feminist art, unacknowledged as such.

The MoMA symposium was sold out weeks in advance. Ms. Lippard and the art historian Linda Nochlin appeared, like tutelary deities, at the beginning and end respectively; in between came panels with about 20 speakers. The audience was made up almost entirely of women, among them many veterans of the women’s art movement of the 1970s and a healthy sprinkling of younger students, artists and scholars. It was clear that people were hungry to hear about and think about feminist art, whatever that once was, is now or might be.

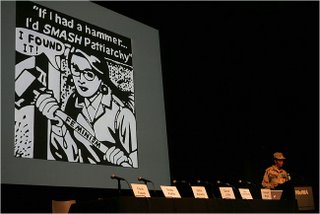

What it once was was relatively easy to grasp. Ms. Lippard spun out an impressionistic account of its complex history, as projected images of art by women streamed across the screen behind her, telling an amazing story of their own. She concluded by saying that the big contribution of feminist art “was to not make a contribution to Modernism.” It rejected Modernism’s exclusionary values and authoritarian certainties for an art of openness, ambiguity, reciprocity and what another speaker, Griselda Pollock, called “ethical hospitality,” features now identified with Postmodernism.

But feminism was never as embracing and accessible as it wanted to be. Early on, some feminists had a problem with the “lavender menace” of lesbianism. The racial divide within feminism has never been resolved and still isn’t, even as feminism casts itself more and more on a globalist model.

The MoMA audience was almost entirely white. Only one panelist, the young Kenyan-born artist Wangechi Mutu, was black. And the renowned critic Geeta Kapur from Delhi had to represent, by default, all of Asia. “I feel like I’m gate-crashing a reunion,” Ms. Mutu joked as she began to speak, and she wasn’t wrong.

At the same time one of feminism’s great strengths has been a capacity for self-criticism and self-correction. Yet atmospherically the symposium was a very MoMA event, polished, well executed, well mannered, even cozy. A good half of the talks came across as more soothing than agitating, suitable for any occasion rather than tailored to one onto which, I sensed, intense personal, political and historical hopes had been pinned.

Still, there was some agitation, and it came with the first panel, “Activism/Race/Geopolitics,” in a performance by the New York artist Coco Fusco. Ms. Fusco strode to the podium in combat fatigues and, like a major instructing her troops, began lecturing on the creative ways in which women could use sex as a torture tactic on terrorist suspects, specifically on Islamic prisoners.

The performance was scarifyingly funny as a send-up of feminism’s much-maligned sexual “essentialism.” But its obvious references to Abu Ghraib, where women were victimizers, was telling.

In the context of a mild-mannered symposium and proposed visions of a “feminist future” that saw collegial tolerance and generosity as solutions to a harsh world, Ms. Fusco made the point that, at least in the present, women are every bit as responsible for that harshness — for what goes on in Iraq for example — as anyone. read the whole article

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home