African Comics, Far Beyond the Funny Pages , NYTimes

“It’s intense,” said the security guard as I was leaving “Africa Comics” at the Studio Museum in Harlem after an hour or more of up-close looking and reading. She was right. That’s exactly the word for the stealth-potency of this modest, first-time United States survey of original designs by 35 African artists who specialize in comic art.

Their work is intense the way urban Africa is intense: intensely zany, intensely warm, intensely harsh, intensely political. True, you could say the same of New York or New Delhi, or any major cosmopolis being shaped by globalism these days. Yet every place has very specific intensities. Africa does, and they are distilled in the art here.

I guess there are people who still can’t fit the idea of “art” and “comics” into the same frame. But why? If handmade, graphically inventive, conceptually imaginative images — which describes practically everything in this show — aren’t art, what is? The same images are topical, and are meant to be seen in reproduction; does that alter their status as art? Goya, Daumier and José Guadalupe Posada would of course say no.

In any event, Pop Art and all that followed it long ago wiped out the notion that comics are one-liner sight gags good only for the “funny pages.” “Masters of American Comics,” the ambitious historical survey split between the Jewish Museum in Manhattan and the Newark Museum, is truly a masterpiece show. “Africa Comics” edges into that territory, as does some of the work in a tiny show ending Dec. 17 called “Political Cartoons From Nigeria” at Southfirst, a contemporary gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Not that entertainment is missing from the Studio Museum selection. Just the opposite: some of the material is just plain fun. We are on familiar Marvel Comics ground with the adventures of the charismatic Princess Wella, a kind of superwoman with a ceremonial staff and braids, created by Laércio George Mabota, a young artist from Mozambique.

And even a non-African can see why the schlumpy but wily character named Goorgoolou — in a series by Alphonse Mendy, who goes by the name T. T. Fons — has become a national hero, or antihero, in Senegal. With Ralph Kramden-esque panache, he lampoons social pretensions and embodies the plight of an everyman in a baffling postmodern world. Such is the character’s fame that a television show and magazine have been built around him, and he was a star of the recent international Dakar biennial, Dak’Art, where comic art, for the first time, took center stage.

Yet far more often than not, humor is a sugar-coating for disquiet. For example, a piece by the South African artist Anton Kannemeyer, who goes by the name Joe Dog, uses a charming children’s book style — the source is “Tintin au Congo” from the classic Belgian series, its racial stereotypes deliberately left intact — to depict a black-on-white racial attack that turns out to be a paranoiac neocolonialist dream.

Mr. Kannemeyer is a founder, with the artist Conrad Botes, of the graphic magazine Bitterkomix, which has tackled some of the most pressing political issues in a still volatile South Africa. And in general African politics and popular culture are inseparable. Most of the comics in the Southfirst show are direct attacks on past and present governmental corruption in Nigeria, and nearly all of them are by Ghariokwu Lemi, an artist famous for having painted 26 album covers for the Afrobeat idol and political rebel Fela Kuti.

In some comic art, political content takes an upbeat, utopian tack. More than one piece at the Studio Museum evokes scenes of ethnic violence in order to propose an alternative vision of peace and solidarity, exhorting a new generation of Africans to learn from the mistakes of their parents.

More often the tone is skeptical, even sardonic, as in the case of a sly, graphically jazzy account by Didier Viode, an artist from Benin now living in France, of the bureaucratic roadblocks encountered by Africans applying for immigration papers. Or in a depiction by the Ivorian artist Maxime Aka Gnoan Kacou, known as Mendozza y Caramba, of a noctural mugging as an elegant shadow play in black and gold against a solid blue ground.

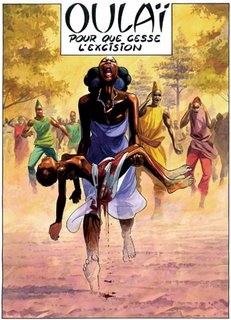

Visually neither style is intrinsically “serious.” You can’t know at a glance what you’re getting into. By contrast, right from its opening image — of a screaming woman carrying a bloodied child, done in full-blown social-realist style — there is no mistaking the didactic content of a story of female genital mutilation by the Senegalese artist Cisse Samba Ndar.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home