Chelsea Is a Battlefield: Galleries Muster Groups NY Times

IN case you haven’t noticed, the summer group show wars are raging in Chelsea. Over the last few years they have become something of an annual rite. Starting in late June and continuing through August, the solo shows drop off and the group shows — four or more artists — proliferate. The densely packed yet oddly discrete parallel universes in which galleries exist for most of the year lose some of their definition.

After all, proximity breeds a lot of things, including competitiveness, as well as pressures that need venting, and that seems to be what summer in Chelsea is for. It is open season for cool hunting and power gathering. Hipness prevails over blue-chipness.

Galleries let off steam, kick up their heels, make plays for new artists or higher profiles, or try to improve their standing. Their inner lives are more fully visible, not the least because group shows involve more decisions than the solo kind. There are more artists and more art and, frequently, outside loans and curators, all multiplied by the 100-plus group shows Chelsea has fostered this summer. Even a small sampling of these shows, as here, gives some indication of the tremendous amount of data about current art and the scene that is being released into the atmosphere.

A Few Signposts

The exhibition titles alone can trigger a kind of semiotic delirium, and in many cases are a show’s main cleverness. Some are deliberately provocative: “Better Than Sex, Better Than Disneyland” at Ramis Barquet, “Binge and Purge” at Magnan Projects “Photography Is Not an Art!” at Alan Klotz and “Montezuma’s Revenge” at Nicole Klagsbrun. Some form odd chains of words and ideas: “Men” at I-20, “Men and Materials” at Jeff Bailey, “Materiality” at Kravets Wehby, “Material Abuse” at Caren Golden.

Others may fill gaps in your liberal arts education: Wallace Stevens’s Whitmanesque ode to summer has provided the title for “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts,” a group show at Mitchell-Innes & Nash. Organized by the photographers Justine Kurland and Dan Torop, it elegantly and peripatetically spans 140 years of photography: the rabbit pulled out of the 19th century’s hat. And there is always a high-water mark of pretentiousness. This year’s is the title of the Bortolami Dayan show, “War on 45/My Mirrors Are Painted Black (For You).”

Other Attributes

Titles aside, the first key to the import of a summer group show is its organizer. Is it an invited guest (curator, critic, artist, dealer) with a reputation of a certain weight and possibly a foreign passport? Or is it the gallery’s owner or junior staff?

Equally important are the artists selected: Are they young and hot — like a fishing expedition or football draft — or are the generations mixed so as to reflect flatteringly in all directions? And how many artists in the show are already represented by the host gallery? Too many and it can seem overly promotional. It’s usually a judgment call. A borderline example: In Cheim & Read’s marvelous show about Chaim Soutine and modern art, 5 of the 20 artists whose work share the walls with the Soutines are represented by the gallery.

When the guest curator is an important artist, a courtship may be under way, or complete. For example the exhibition organized by Charles Ray at Matthew Marks is the first public sign that Mr. Ray, the prominent American sculptor, has joined this prestigious gallery. That the show includes loans from the Museum of Modern Art (a tall Giacometti figure) and the Whitney (an important early Mark di Suvero) reflects Mr. Marks’s clout, the museums’ interest in Mr. Ray, or both. But let’s move on to other cups of tea leaves.

An Aesthetic Divide

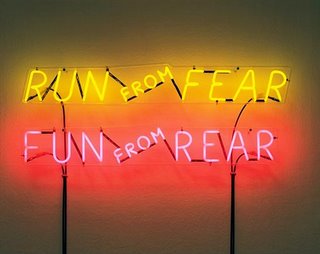

Chelsea’s group-show summer fray can evoke a farmyard with a surplus of roosters. This was especially the case last summer when male artists and curators seemed to dominate, along with a plethora of Conceptually-based black-on-black appropriation art. At the time the term “boys in black” came to mind, and to a certain extent they’re back.

This summer’s crop of shows confirms that an opposition present in art since the mid 1970’s is still in force, if a bit out of whack. In the 1980’s appropriation art and Neo-Expressionist painting were fairly evenly matched, which made for a really invigorating argument. These days Conceptually-based appropriation art — involving photographs, found objects, text, elusive meaning and usually not much in the way of form — has taken over some of Chelsea’s sleeker galleries. While art that is more robust, colorful, physical and sometimes painterly tends to be found in less prominent shows, like “Diamonds Cut Diamonds” at Rare, where the work of five young sculptors exudes a material flamboyance that is curtailed by a banal sense of realism. Read the full article.